The Mother Art Prize 2020

- Nov 8, 2020

- 5 min read

Celebrating women artists

by Madeline DeFilippis | 8 November 2020

In late September, I received an email from my tutor, telling our class that a former student of hers was involved in a show called the ‘Mother Art Prize’. In its third year, the Mother Art Prize is run by Procreate Project and is ‘the only international open call for self-identifying women and non-binary visual artists with caring responsibilities’. The prizes associated with the exhibition are supported by major art galleries and institutions including Whitechapel Gallery, Tate Modern, Frieze London, Richard Saltoun, and more. I hear about shows associated with these museums and galleries regularly. So, why didn’t I know about the Mother Art Prize? When Linda Nochlin asked, ‘why have there been no great women artists?’ in 1971, she highlighted a disturbing lack of academic and critical writing on women artists throughout history. Since then, through global Women’s Liberation movements and the work of feminist scholars, writers and activists, we in the art world have significantly improved our historical understanding of women artists in the historical record. However, women artists were, and still are, expected to also fulfil the traditional, cisgender and heteronormative role of the woman as a carer. Women artists are scrutinized much more severely than their male contemporaries for what they do in personal lives, specifically whether or not they choose to have children during their careers. Claire Mander, the founder of CoLAB, an independent curatorial practice and a Courtauld alumna, is a Trustee of UK Friends of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and was on the judging panel of the Mother Art Prize. She claims, I think rightfully so, that motherhood is a ‘taboo topic in life and in art’. ‘Even within the community of women’, she says, motherhood is an embarrassing topic to approach, and what’s more, it is ‘chronically undervalued as an occupation’. This notion of motherhood as ‘work’ has only recently (in the last fifty years) been acknowledged by the wider public. As far back as 1969, when Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b. 1939) wrote her ‘Maintenance Manifesto’. In the manifesto, Laderman Ukeles proposed an exhibition called ‘Care’, in which ‘pure maintenance’ would be exhibited as contemporary art. Confronting her work as an artist and her work as a mother, Laderman Ukeles decided to exhibit her own work as a mother and an artist as her performance art, shedding the invisibility of her work as a mother and declaring that this work was worthy of artistic value.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Washing/Tracks/Maintenance – Outside, July 22, 1973, Wadsworth Atheneum of Art, Hartford, CT.

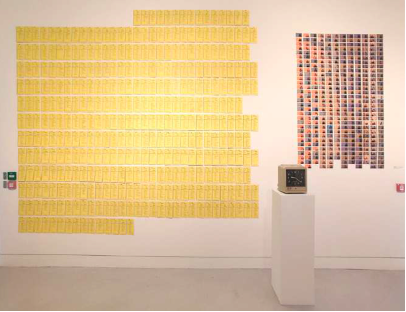

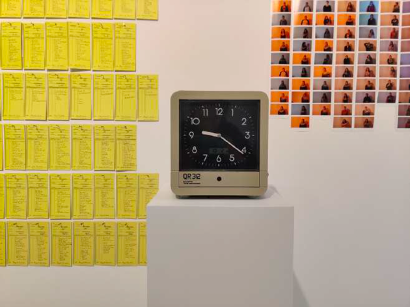

Motherhood is a durational performance, Mander points out, and this contributes to its invisibility. ‘Time’, she said, is the biggest barrier to women artists and their success. This brought me back to one of my favourite pieces at the Mother Art Prize exhibition, by Carly Schmitt. Her work Re-enactment of a ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE, 2019-2020 consists of 365 punched timecards which she wrote on everyday detailing the work she did as a mother. The obvious irony is that mothers do not punch timecards, nor are they paid for the work they do each day. Schmitt priced the work at £30,000, the average yearly salary of a childcare worker.

Carly Schmitt, Re-enactment of a ONE YEAR PERFORMANCE, 2020.

Stepping into the 2020 Mother Art Prize exhibition, I was blown away by the conceptualism, the aesthetics, and the emotions with which these pieces were imbued. The finalists, a group of twenty artists (out of 626 applications, from 45 countries) ranged in age, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, ethnicity, and more. There was sculpture, multimedia work including audiovisual, audio, and photography, and textile work. When I talked to Mander about how women artists’ use of textiles (often referred to as a ‘female’ material and/or process) can be denigrated, she pointed out that there are some well-known textile artists with great fame, such as Anni Albers, who received a retrospective at Tate Modern in 2018. However, she said, textile work is still regarded as a ‘secondary skill’. Much like the rest of the work of motherhood, the skill and the talent possessed by women is voided because of its cultural association with women, and this, Mander says, leads to a ‘lower value in general’ of work by women artists in the art market. How do we augment the value of work by women artists? ‘We need more women buyers’, says Mander. Equity is inescapably the crucial aspect to achieve in our society in order to level the playing field.

Clearly, the personal is political. From Linda Nochlin, to Griselda Pollock and Laura Mulvey, art historians have shown that female artists are yet to be appropriately probed, let alone celebrated at the level of canonical male artists by the discipline and by the museum-going public. Fifty years on from Linda Nochlin’s essay, exhibitions such as Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists, 1900-1950 in 2018, and the Artemisia exhibition at the National Gallery this year, attempt to function as correctives to this historical denial of women artists. All around the world, museums are utilising the new decade as a chance to celebrate more women artists. The Baltimore Museum, for example, promised in 2019 that they would only purchase new pieces from women artists in 2020. The Serpentine Sackler held a survey exhibition of Luchita Hurtado’s works in 2019, an artist for whom work as a mother came first.

What I took away from the Mother Art Prize, and the conversations I had with my peers after seeing it, was that motherhood is indeed still undervalued in our society, financially and socially. It can be a great inspiration for artists, but also a physical barrier to practicing art. We must also remember that women artists, be they mothers or not, have an incredible perspective on the world as it is today. Sabba Sial Elahi (the suspect is my son (series), 2018) utilises felt embroidery to examine the surveillance and dehumanisation of Muslim bodies; Lauren Pisano (Packaging Yourself (series), 2020) appropriates the words of John T. Molloy’s 1975 book The Woman’s Dress for Success Book, highlighting sentences like ‘Wear only skin-colored pantyhose. Anything else at work is unthinkable. Furthermore, anything else turns off men’ through her photo series. The winner of the Mother Art Prize, Jude, 2020 by Helen Benigson, is a 25-minute video delving into the life and ‘transformation of an Orthodox Jewish Rebbetzin (Rabbi’s wife) in a British Synagogue to a single, nonbinary person’. These works are inspirational, witty, satirical, and poignant, and deserve as much (if not significantly more) attention than the traditional and canonical heterosexual, white cisgender men of the Western art historical tradition.

Coral Woodbury, Revised Edition, 2020 – ongoing