Anne Tallentire and the Politics of the Domestic at Kettle’s Yard

- The Courtauldian

- Sep 28, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 1, 2025

Natasha Phillips-Geen

From March to July this year, Kettles Yard Gallery brought together a display of artists who, in the words of the show’s creator Amy Tobin, ‘offer vantage points to a world in perpetual crisis.’[1] Though modest in floor plan, the perspectives offered by these eight artists for exploring what it means to make art in a world of ‘domination and conflict’ were expansive. Titled Here is a Gale Warning, works ranged from Candace Hill-Montgomery’s experimental hang-strung weavings, named after figures as diverse as Brice Marsden and George Floyd, to Tarek Lakhrissi’s collection of metal spears populating the ceiling space, referencing Monique Wittig’s amazonian war-of-the-sexes novel Les Guérillères — and to photographs of Celia Vicuna’s precarios, painstakingly arranged miniature vignettes of found materials inhabiting brutal, unrelenting urban environments.

Geographically as well as conceptually broad, the eight artists occupied sites ranging from Arctic tundra to Battersea Power Station. But it was Anne Tallentire’s two works that felt most grounded in the space itself. Positioned at a low level, her sculpture stood no more than 30 centimetres high, accompanied by a constellation of intersecting lines of heavy-duty tape mapped out on the floor.

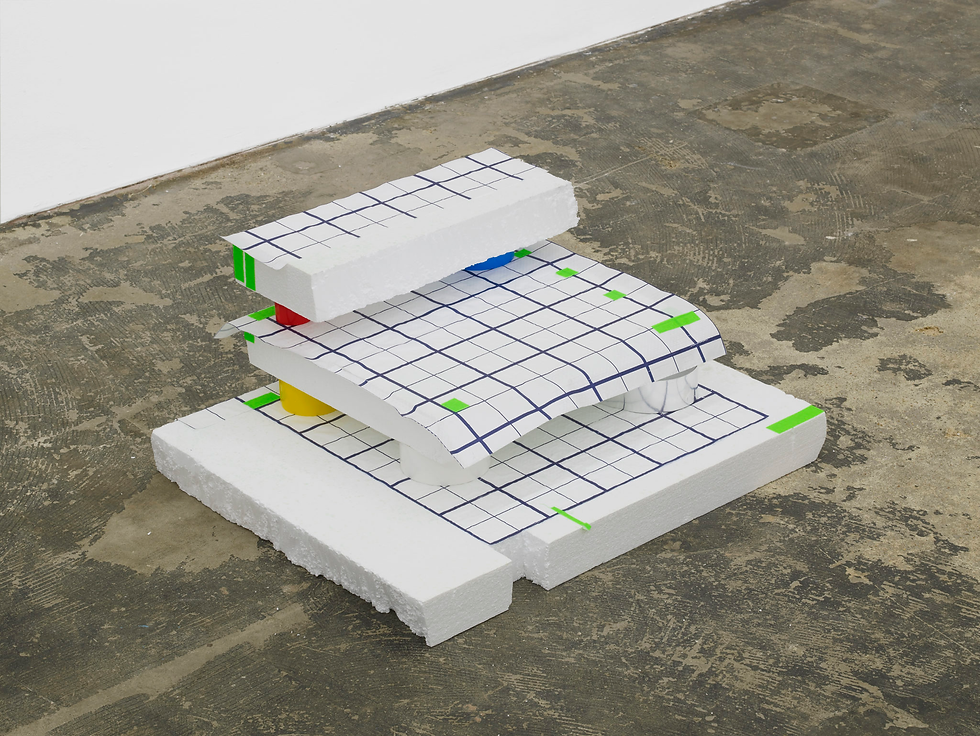

Tallentire’s sculpture occupies the central floorspace of the first room of the exhibition, where rectangular polystyrene sheets with gridded paper layered on top were stacked in between rolls of primary coloured tape. The assemblage of materials was first devised in 2018 as part of her series Interspacing. The series scales down the measurements of unknown domestic interiors and sites of confinement and translates the measurements onto materials more often associated with construction: tape, ecoscreed insulation boards, plastic film, which are then cut out. These shapes are then placed on top of one another, with entire rolls of tape between each sheet, creating a stacked structure. By imposing the spatial restrictions of domestic urban living onto utilitarian materials, largely only accessible for industrial and construction purposes, the conventional experience of domestic space is inverted.[AT1] [PN2] The constraints of domestic construction are now made overtly visible.

Instead of being enveloped — or constrained — by the room itself, we are invited to look directly at the constructedspace[AT3] [PN4] presented before us. Here, the physical dimensions of the room no longer dictate or restrict our experience. Instead, we are asked to consider the implications of domestic space and scale from an abstracted viewpoint. We look at the physical scale of domestic construction rather than being shaped by it[AT5] . The random nature of the visible materials, combined with the sculpture’s deliberately unfinished quality. Green gaffer tape visibly binds wallpaper to adjoining polystyrene, encouraging us to reflect on the possibilities of change and reconfiguration beyond the strict dimensions assigned to the sheets of polystyrene themselves.

The sculpture is devoid of specificity. The furniture or domestic utilities that informed the dimensions of the polystyrene and sheeting that Tallentire cut are unknown to us. The ‘space’ the sculpture presents is not a personal one, neither to the viewer nor Tallentire herself. It is instead a sculpture acutely informed by economic and design factors. The measurements of the polystyrene sheeting are cut to match scaled-down dimensions of preexisting objects [AT6] specifically designed for domestic consumption. Beds, chairs, and sinks are just some of the objects Tallentire used to form the measurements of her sculpture, drawing attention to the standardised systems that inform domestic space and patterns of living.

Tallentire’s work is acutely political. By exploring the materials associated with construction and building, Tallentire seeks to investigate how, shaped by social and economic forces, they manifest themselves in the urban environment. Throughout her career, Tallentire has used site-specific installations and to consider the monumental questions of collective and private space, and the concept of occupying space and its boundaries and thresholds. It is clear from her speaker appearance at Kettles Yard this July in honour of the closing of Here is a Gale Warning, that questions of affordable housing, access to the simplicities of light, ventilation, quietness are [AT7] themes at the forefront of her current practice. In this appearance, in conversation with Tobin, Tallentire also stressed her concern at the erosion of the ‘third space’[AT8] in urban neighbourhoods like her own in North London. Tallentire cited diminished public services and ill-considered building projects resulting in a lack of alternative space to occupy beyond work and home, particularly for young people. The awkwardness of modern urban living, exemplified by the erosion of the age-old trifecta of workspace, home space and third space, was likely then considered in the making of the sculpture, not least in its title Interspacing.

Writer and curator Sara Greavu identifies awkwardness as a recurring theme in Tallentire’s practice, a quality that also feels subtly reinforced by curatorial decisions at Kettles Yard. The sculpture, placed directly on the floor at the centre of the exhibition space with no barrier or demarcation, feels oddly exposed. One careless step backwards while admiring Justin Caguiat’s epic abstract painting, which hangs immediately behind, and the whole sculpture would — inevitably — be crushed.

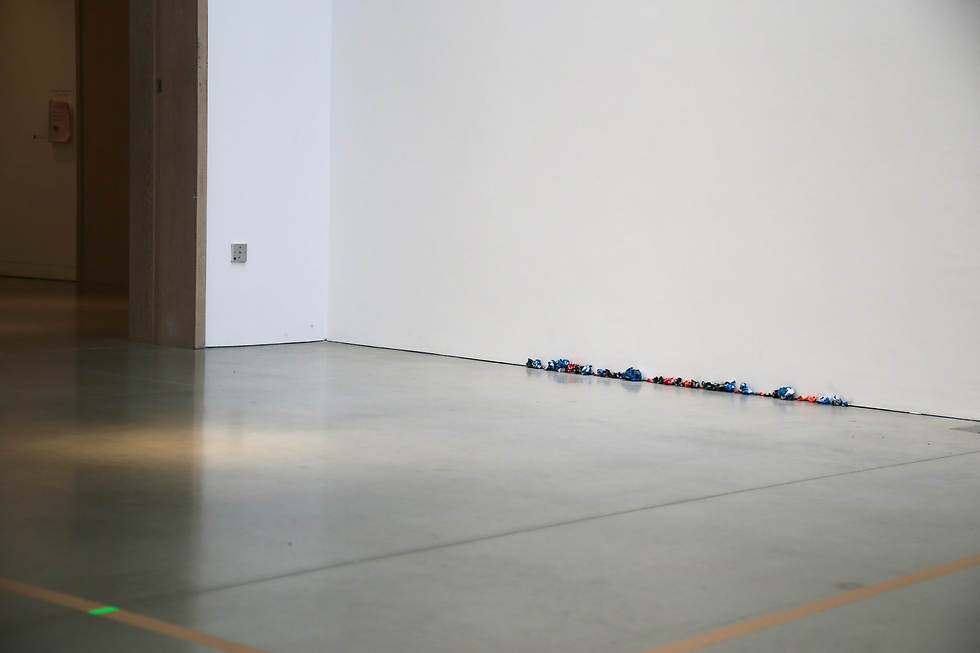

The force of the human body to affect artwork becomes more inevitable in Tallentire's large-scale drawing commissioned for the exhibition on the floorspace which surrounds her sculpture. The use of heavy-duty tape is repeated from Interspacing and is also stuck down on the floor in a series of shapes, designed to be repeatedly walked over by exhibition visitors to view other works on display. The shapes mark out the exact floor plan of a flat a few streets away on a Kings Street. The flat was the result of a collaboration between Cambridge City Council and Cambridge university in 1976 in an effort to build more affordable housing in Cambridge. The collaboration between the council and the university on housing was a rare one, and undoubtedly, to many visitors of the gallery, feels insignificant in a city with an average house price of £508,000, a chronic shortage of social housing and a historic social town-gown divide that remains present.[2]

The paradox of choosing to display and highlight such a rare project in the Kettles Yard Gallery, a space itself owned by the university, seems to add a productive tension to the work and makes us question and reconsider its environment, rather than diminishing its validity or interest. More interesting is how Tallentire's process disrupts traditional processes of creating space and reconsiders the role of drawing in architecture.

In his seminal book Words and Buildings, architectural historian Andrian Forty describes the conventional process of architecture as a linear sequence[AT9] [PN10] : idea – drawing – building – experience – language.[3] Tallentire’s process reconfigures these steps to force us to interact with the idea of a domestic environment in new ways. Rather than an architectural drawing it acts as a two-dimensional, primarily visual, multisensory guide towards what space the unrealised architecture will create. Tallentire’s drawing allows us to inhabit a preexisting space, a floor plan drawing produced as a result of, rather than to inform, a domestic function. Like much of Tallentire’s work, the drawing is informed by the actual condition as opposed to a prospective vision. It encourages consideration of the sequential approach to the creation of housing and results in a work which, like the urban environment, is affected by human patterns of behaviour and movement, despite its strict lines and demarcations.

The work culminated in its deinstallation, which happened on the last day of the exhibition in July with the public invited to a deinstallation performance. Here, Tallentire’s assistant methodically peeled back the tape on the floor, scrunching it into crumpled balls that were lined up against the wall. The drawing is thus translated from a two-dimensional state to a three-dimensional structure. There is, however, no end product – no completed structure ready for inhabitation. Instead of an architectural drawing that results in a realised three-dimensional space, Tallentire takes a space and translates it back to a drawing. A drawing which has now been affected by not only the physical presence of the flat it represents, but also by the space and people who have ‘inhabited’ the drawing its lifespan of a few months at Kettles Yard.

As the final strips of tape were pulled from the floor, the tape clung more stubbornly than at the beginning, forcing Tallentire’s assistant to increase the strength of each peel. The sound shifted, sometimes slow and drawn out, other times quick and high-pitched, echoing the uneven wear of visitors’ footsteps over the months. As Tallentire later explained, the tape’s resistance reflected the differing levels of pressure and movement it had absorbed, embedding traces of human presence into the work itself.

Tallentire's offering at Kettles Yard allows us to engage with domestic space in a way that transgresses conventional urban experiences. We are encouraged to look into, rather than around, the domestic space and walk over boundaries and parameters that the built environment makes physically impossible. It is a drawing style that is unique, it allows us to inhabit its negative space, cross over its lines and ‘see’ space in ways an architectural floorplan does not. In removing the tape from the floor and returning to work to a collection of gathered materials, Tallentire reminds us that domestic environments are not fixed but rather remain sites of contact and negotiation and boundaries.[AT11]

Bibliography

Cam.ac.uk. “Here Is a Gale Warning: Art, Crisis & Survival,” 2025.

Forty, Adrian. Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Greavu, Sara. “The Gap of Two Birds.” In Anne Tallentire, 61–71. Belfast and Southampton: The Mac and John Hansard Gallery, 2023.

Moody, Oliver. “Cambridge Is a ‘Divided City’ as University Tightens Security and Shuts the Public Out.” Thetimes.com. The Times, April 16, 2014. https://www.thetimes.com/uk/article/cambridge-is-a-divided-city-as-university-tightens-security-and-shuts-the-public-out-w8ntx3tdsj3.

Tobin, Amy, ed. Here Is a Gale Warning. Cambridge: Kettle’s Yard, 2025.

www.ons.gov.uk. “Housing Prices in Cambridge,” April 17, 2024. https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/housingpriceslocal/E07000008/.

[1] “Here Is a Gale Warning: Art, Crisis & Survival,” Cam.ac.uk, 2025, https://www.kettlesyard.cam.ac.uk/whats-on/here-is-a-gale-warning-art-crisis-survival/.

[2] “Housing Prices in Cambridge,” www.ons.gov.uk, April 17, 2024, https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/housingpriceslocal/E07000008/; Oliver Moody, “Cambridge Is a ‘Divided City’ as University Tightens Security and Shuts the Public Out,” Thetimes.com (The Times, April 16, 2014), https://www.thetimes.com/uk/article/cambridge-is-a-divided-city-as-university-tightens-security-and-shuts-the-public-out-w8ntx3tdsj3.

[3] Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000), 32.

Comments